Trade associations are the voice of thousands of Dutch companies in the political arena in The Hague. Where traditional media is an often used tool to make the voice of the association’s members heard, Public Matters was curious to see to which extent trade associations use social media in their lobbying. After all, many social media channels enable users to reach specific target audiences. Politicians are very active on the various social media platforms and often use this tool to put issues on the political agenda, or to gather input from the field.

Public Matters looked into the social media activity of 50 Dutch trade associations from the 18 largest economic sectors, including hospitality and mobility. How do these sectors and their individual sector organizations use Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn? And what opportunities do these platforms offer to influence policy? Two fixed moments in 2019 and 2020 (before and during the corona crisis) were taken as a starting point, to determine a correlation between COVID developments and the use of social media.

This article focused on Twitter, as it is the most widely used social platform used as a lobbying tool. In addition, of all the social media platforms, trade associations are most active on Twitter. At the end of the article, a brief overview of the activity of trade associations on LinkedIn, Instagram and Facebook is included.

Research method

To determine how influential trade associations are, we conducted an analysis in which trade associations were divided into four profiles in their use of social media. These are:

1. The inactive profile: the trade association has an account but uses it only sporadically or not at all.

2. The observing profile: The trade association uses social media mainly to follow news and to stay informed of developments in the sector, and sometimes to retweet or share messages from other organizations.

3. The professional profile: The trade association shares a lot of news about the sector and its own activities, such as working visits and conferences, but also shares news items and messages from politicians and ministers.

4. The influencer profile: The trade association is very active on social media and not only shares messages about its own work and the sector, but proactively puts issues and standpoints on the agenda and subsequently engages in online debate with politicians, ministers and key opinion leaders.

Besides the classification into four profiles, the influence score was also measured. This involved looking at the reach of the average tweet based on the number of reactions, likes and retweets. The higher the score, the more dialogue on the subject there is among followers, and the greater the influence on the network via Twitter’s algorithm. The score ranges from 0 (no influence) to 200 (maximum influence). The influence score of the average industry organization is 19.8 (measured mid 2021). |

Capturing the voice of the members in one Tweet

Many trade associations use Twitter as an additional channel to communicate with their members, as the tool is more flexible compared to traditional newsletters. The goal of their social media messaging often is to inform members and other stakeholders in the sector. However, it also offers the opportunity to influence the political and public debate. In fact, Twitter is mainly used to share news and political decisions. The platform is frequently used by politicians, ministers, journalists and key opinion leaders. In general, Twitter can be seen as a platform where opinions are shared as well as shaped.

Using Twitter as a lobbying tool

Following this, Twitter is an excellent platform to amplify the voice of members. 149 out 150 members of parliament who are active on Twitter, as well as ministers and their online spokespersons, use the medium to gather input for political decision-making and to gauge the sentiment on policy proposals among the wider public. If a trade association succeeds in generating ample visible support for its plans through Twitter, it can use this support to influence political debates. Some examples of how this can be achieved:

- Call on members to follow, like, and share all sector channels and messages on social media. The power lies in the amount of interaction with a post or tweet. The more interaction, the higher Twitter’s algorithm will push the tweet in the timeline of followers. Also, make sure that the relevant decision-makers follow your trade association by following, liking, and retweeting posts yourself.

- Share links to social media channels and news in newsletters, on your website and in WhatsApp groups with members.

- Draw up a Twitter plan for members: which policymakers or key opinion leaders should they follow, like, tag, or address? When should they post? What language and tone of voice do they use? What are the do’s and don’ts? And what hashtags do they use to make a topic uniformly trending?

- Actively Tweet during political debates (i.e. about the input of the sector organization or the results of the debate). You can also address members of parliament by tagging them. This way you can share successes, and you can influence the (online) debate.

Twitter used mainly as a ‘professional’ profile

Our analysis shows that many trade associations use Twitter as a ‘professional’ profile. The Twitter accounts provide policymakers and members with a good insight into the activities of the association or into the trends within the sector. If associations have the right followers, Twitter offers an extra tool to inform external stakeholders about the association’s activities. This often means that messages from the association’s own website or other media are ‘pushed’ via the Twitter channel.

Twitter rarely used for political lobbying

It is striking that trade associations only sporadically use their Twitter channel for political lobbying or to really enter a discussion and gather information (the ‘pull’ variant, reaching out to the target group). Yet Twitter is the medium where industry organizations, politicians, and other stakeholders can communicate freely. And in addition to this, Twitter offers the possibility to communicate the concerns or wishes of an organization transparently and publicly to politicians. Unlike individual companies for whom social media is more linked to marketing and corporate communications, trade associations have more leeway to communicate publicly on behalf of their members. And in some cases they need to show members that they are publicly promoting their interests.

Corona crisis generates ‘professional’ and ‘influencer’ profiles

However, the analysis also shows that since the emergence of COVID-19, several trade associations several trade associations with “inactive, observer or professional” profiles started showing characteristics of an “influencer” profile. The hospitality industry is a good example of this. During the corona crisis, they adopted an increasingly activist tone in their social media communications and proactively called on government ministers not to implement the proposed corona measures. Often supported by hundreds of reactions, likes and retweets from the sector. Unfortunately in this specific case, this was no guaranteed success.

Trade associations from the sports, healthcare, and mobility sectors are also increasingly using Twitter to address the adverse effects of corona measures. Several examples:

The fitness sector

From March to June 2020, the branch organization NL Actief (branch association of recognized sports and exercise companies) used Twitter to plead for the reopening of gyms as quickly as possible. They did this with the help of influencers in the field of sports and healthcare such as Arie Boomsma ( a well-known Dutch sporter) who were visible both online on social media and TV programs such as Op1 and Jinek (Dutch current affairs programs). Such offline moments were also widely shared online, such as a BNR news radio fragment in which NL Actief’s director Ronald Wouters argued in favor of accelerated opening. Spreading such lobby messages from more traditional channels to social media such as Twitter can generate a lot of likes and shares and thus strengthen the lobby message’s credibility and impact.

As the crisis continued, it became increasingly clear that COVID-19 patients with an unhealthy weight were at greater risk of a more serious course of the disease. NL Actief responded cleverly to this on Twitter. In addition to the branch association’s logical plea on Twitter for an extensive support package for fitness entrepreneurs, studies were also shared on the platform that showed that one out of three people have started exercising for health reasons in recent years. Calls by State Secretary Blokhuis (Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport), Minister de Jonge (Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport), and Intensive Care specialist Diederik Gommers to pursue a healthy lifestyle were also widely shared by NL Actief. In addition, the trade association cleverly capitalized on the worldwide social media campaign #letsmoveforabetterworld and created unity among its followers by using the hashtag #samensterk.

- The gyms were eventually completely closed from the start of the first lockdown (15 March 2020) until 1 July 2020, although the original plan was to keep the gyms closed until 1 September 2020. On 15 October 2020, the Netherlands entered the second lockdown period. As late as 15 December 2020 the closing of gyms followed, which was two months later than during the first lockdown period.

The mobility sector

In 2020, trade associations from the transport sector, including KNV and the Mobility Alliance, pleaded on Twitter for the expansion of transport capacity and the financial compensation for cancelled trips, and supported this with research. For example, a Roland Berger report in May 2020 entitled “Long-term impact of COVID-19 on mobility” (commissioned by the Mobility Alliance) showed that a rapid return of the (old) mobility problems was imminent if transport capacity was not expanded. The conclusions of the study were widely shared on Twitter by the Mobility Alliance, as was the live recording of the presentation of the study in Nieuwspoort (meeting center) in the presence of the then Minister Van Nieuwenhuizen (Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management). Later that year, Van Nieuwenhuizen announced increased investment in infrastructure in the coming years. On the relationship between corona and mobility, she said: ‘If the economy picks up and traffic increases again, there are so many reasons you can see that mobility will increase and investments are needed.’ With this, she supported the call of the Mobility Alliance.

Specifically, there was a great deal of media attention in 2020 regarding the continued financial support of healthcare-related transport. This media attention and the urgent letter the KNV sent to the minister on this subject were Twitter messages with a lot of likes.

- After KNV’s letter, Minister De Jonge (Health) wrote to the House of Representatives: “The starting point is to offer turnover guarantees for the period up to 1 June for the healthcare transport sector. This also answers the call of the sector to pay care providers for non-delivered trips and to reimburse additional costs as a result of complying with corona protocols.”

- Transport capacity has been scaled up and down by the Cabinet in 2020, depending on other COVID-measures. In addition, the sector has been compensated several times by means of the availability payment, the last of which has been extended until September 2022.

Culture sector

In the cultural sector, no (new) trade associations seem to have emerged during the corona crisis to promote interests of artists online. A large trade association from the cultural sector, the Federation of Employers’ Associations in Culture (representing the performing arts, museums, libraries, centers for the arts, venues and orchestras) does not have a Twitter page. The trade association Cultuurconnectie (representing cultural education, amateur art and community college work) retweeted news about artists in financial difficulties and reduced income, but did not start an online campaign. The “Taskforce Cultuur” (an ad hoc cooperation between various cultural umbrella organizations, established at the beginning of the corona crisis) also does not have a Twitter page.

On the other hand, private online actions by artists were (more) successful. In September 2020, a well-known Dutch comedian Peter Pannekoek called on the Dutch people on TV to go to the theatre again. Peter Pannekoek’s appeal received a great deal of support on social media. Dutch celebrities and theatre producers broadly shared the appeal. The hashtag #reddecultuur (save culture) also went viral on Twitter. An appeal to Minister Van Engelshoven (Ministry of Education, Culture and Science ) to offer more room for customized work was signed by dozens of cabaret artists.

- Van Engelshoven was heavily criticized, especially at the start of the corona crisis, for her limited efforts for the culture sector. In an AD article (daily Dutch news paper) at the end of 2020, Van Engelshoven said: “I think that criticism has now has faded. All in all, the cabinet is putting 1.6 billion euros into the sector. It is good that the cultural sector stood up for their interests so passionately. The blow they have received is also very great.”

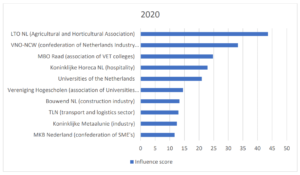

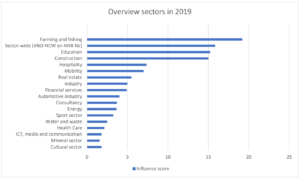

Most influential branches

Although some trade associations started using Twitter (much) more in 2020 and have often even shifted from an ‘inactive’ profile in 2019 to a ‘professional’ profile, this increase is not immediately reflected in the top 10 trade associations with the highest influence score. There, the traditional and larger trade associations generally continue to dominate (both in the pre-coronagraph 2019 and in 2020). This is probably because these trade associations already had their communication budgets, resources, FTEs and online knowledge in order, and could therefore build on their existing online communication strategy that were proven to be effective in previous years. Associations who stand out are the new entries in the top 10 in 2020: Koninklijke Horeca Nederland (hospitality) and Koninklijke Metaalunie (industry), undoubtedly riding the wave of COVID.

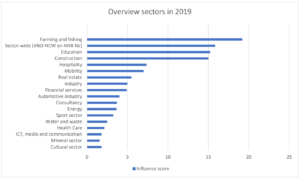

Overview sectors

In total, Public Matters surveyed 50 trade associations from 18 sectors. The influence scores per sector are detailed below. Although to some extent the same conclusion can be drawn as with individual trade associations (sectors that did well in 2019 will also generally do well in 2020), we do see a number of striking developments. In ‘corona year’ 2020, VNO-NCW’s influence on Twitter as a spokesperson for the business community increases compared to the other sectors. In addition, the influence of the hospitality sector increases from 7.3 in 2019 to 22.9 in 2020, and the health sector and the sports sector also substantially increased.

It is also noteworthy that the influence of the cultural sector slightly dropped in 2020. As described above, trade associations from the cultural sector were also remarkably quiet online in 2020.

NOTE: All data in the tables are not a total overview of the scores throughout the year, but have been compiled on the basis of two months per year (May and November 2019 and May and November 2020).

Activity on LinkedIn, Facebook and Instagram

LinkedIn

: Most trade associations post on LinkedIn on a weekly basis, ranging from “in-house” coverage of, for example, the search for new employees, to sharing photos from a work visit, or publishing their own facts and figures about the industry. Two of the 50 trade associations in our sample are not active on LinkedIn.

Instagram: Only 18 out of 50 associations surveyed make use of this medium. In addition, with an average of 180 posts per profile and 1900 followers Instagram can hardly be called an active medium.

Facebook: Although 130 members of parliament have a Facebook account, only half of the trade associations surveyed have an account.

Want to know more?

Would you like to know more about the use of social media within your trade association? Or are you interested in the underlying data? Please contact Machteld van Weede or Nick Spier (Public Matters).